Natto: Japanese History of a Modern-Day Superfood

Natto is often seen as an up-and-coming new superfood in the West, but in Japan natto has been a staple item in the traditional Japanese diet for centuries. While many elements of typical Japanese cuisine (washoku) like miso soup, sushi, tempura, ramen, sake have become well known western culture, natto is an equally common dish that has largely remained obscure. But food culture can evolve rapidly. For example, remember that only a few decades ago, sushi was bizarre and widely reviled; now it is such a familiar part of the American food landscape.

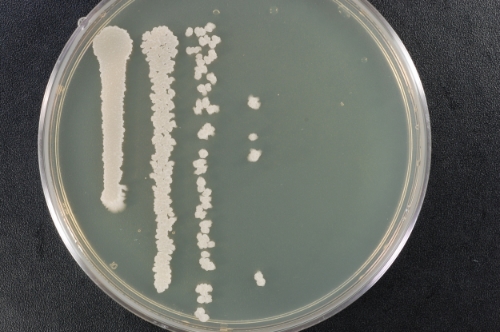

Wide variety of natto sold in Japanese grocery stores

In Japan, natto is most commonly consumed as part of a typical everyday breakfast meal. A hearty morning repast of Natto with rice, miso soup and pickled vegetables could be the Japanese equivalent of a Western standard morning plate of eggs, bacon & toast. Many Japanese eat natto on a daily basis, or nearly so. In a typical grocery store in Japan, one may find dozens of varieties and brands of natto on the shelves. Another good metaphor for natto might be ‘yogurt’: a common, protein and nutrient-dense fermented food category with an entire section of refrigerated space devoted to selections.

The History of Natto

The precise origins of when natto was invented are uncertain. This is often the case with food origin stories, especially those of fermented foods, which were probably ‘discovered’ by accident in cultures throughout the world. In ancient times before refrigeration was possible, spontaneous wild fermentation of foods coming into contact with environmental microbes led to all sorts of delightful ferments: wine, cheese, beer, sauerkraut, coffee and chocolate to name just a few favorites! Fermentation also provided a method to preserve perishable food from spoilage and extend the lifetime of valuable nutritional resources into the lean winter season

The samurai story: Minamoto no Yoshīe

The most popular legend dates natto’s discovery to the 1080’s AD during the Gosannen War, when the great Samurai Lord Minamoto no Yoshīe and his army were traveling towards conquests in northern mainland Japan. One night, the warriors took refuge at a country farm and settled down for a simple evening meal of rice and boiled soybeans, when they got word of an enemy approach. They decided to retreat, quickly wrapping up their food in rice straw they had to feed their horses. The straw provided a natural source of soil-dwelling Bacillus subtilis bacteria to initiate fermentation. Running straight through the night on horseback, the bundles of straw-wrapped soybeans were warmed in the heat and moisture of the horses’ sweat. After reaching safety day or two later, they opened the bundles to discover the soybeans fermented and supposedly found them to be both tasty and nourishing.

Other possible origins

An alternative natto origin story dates an earlier emergence of natto in 7th Century Japan tied to the emergence of Buddhism in Japan. In this theory, Prince Shotoku (574-622 AD) is credited with a similar accidental discovery of natto from a parcel of cooked soybeans wrapped in rice straw. A devout Buddhist scholar, Shotoku is believed to have authored and translated the first Buddhist religious texts in Japanese. Natto eventually became a core protein-rich component of the devotional vegan diet of Zen Buddhist monks, shojin-ryori cuisine. This narrative may also suggest that natto, like so many culinary, cultural and religious ideas, originated in China. Some historians even trace natto’s origins to similar soybean ferments during the Chinese Zhou Dynasty arriving in Japan in the Yayoi period (300 BC – 300AD)! One thing is for sure, Natto has been a part of Japan’s washoku for a very long time.

Natto’s Popularity in Japan

Natto’s popularity spread gradually, starting from the region of Mito city in Ibaraki Prefecture, where the legend of Minamoto no Yoshie took place. Today, natto is eaten by many millions of people on a daily basis, and consumption is highest in the eastern and northern parts of Japan. By the 17th Century start of the Edo period, natto was well incorporated into everyday cuisine with walking vendors selling fresh, locally made wara natto in the streets each morning.

In Edo Japan, natto became a nutritious staple food of the working class, typically eaten with rice and pickles or mixed into miso soup (natto-jiru: see our previous blog post for recipe). At first, natto was made and eaten mostly in the cooler fall and winter months when the nattokin cultures seemed to grow best. As better understanding of how to control the nattokin fermentation in warmer weather developed, makers began producing natto year-round.

Mito: the Birthplace of Natto

Approximately half a million tons of natto are made and consumed annually in Japan, a country smaller (though admittedly more crowded) than the state of California. Historically, the Mito region was also the center of natto production, as the area also happened to be where many farmers grew small soybeans best suited for making natto. Today, Mito city identifies as the birthplace of natto and remains the epicenter of natto culture in Japan.

Ann with the wara statue in Mito

In 2017, I made a pilgrimage of sorts to Mito to learn more about the origins of this Japanese food and to visit some shokunin, the oldest artisanal makers of natto still producing with traditional methods rarely seen elsewhere. Small producers may also make seasonal specialty natto products; for example, natto mixed with pickled vegetables or dry natto.

For example, in Mito one can still buy natto packaged in old-fashioned rice straw bundles (wara) instead of the environmentally unfriendly styrofoam boxes that are the ubiquitous elsewhere. Upon arriving in Mito, I was greeted by a giant metal monument dedicated to natto, in the shape of a natto wara just outside the train station!

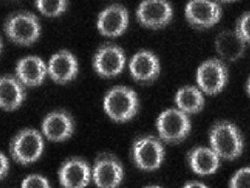

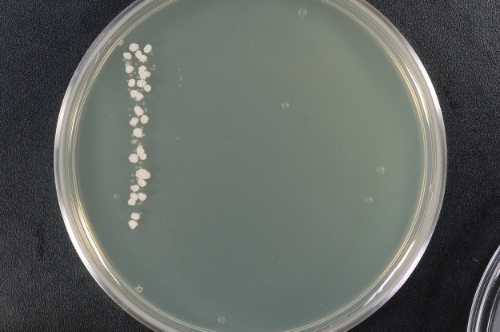

Just like in the legends, for centuries natto was actually made with rice straw as the natural source of fermenting Bacillus subtilis bacteria. Bundles of straw (called wara) were wrapped around small amounts of boiled soybeans and incubated in a warm environment to ferment. In rural areas some DYIers still make natto at home using straw wara6, but this method is no longer widely used in commercial natto production because of fermentation variability and potential for food contamination. But in homage to history, a handful of makers still produce limited edition wara natto, usually purchased as a souvenir or gift item.

Japanese Natto Today

I was fortunate to meet Mito native, natto advocate and entrepreneur Miyashita-San, who brought me to the primary remaining producer of wara, Mito Natto. The basics of natto making are dictated by the biology of the fermentation and are therefore pretty similar everywhere, but each maker adds their own variations in materials and methods to give their products a unique character. It was inspiring to see how every step of the natto process was still done by hand here, including careful packing of the straw wara.

To ensure safe, reliable product fermentation, now all natto commercially produced in Japan is made using purified nattokin starter cultures. Here, already inoculated soybeans filled inside bundles of pre-sterilized wara straw. This natto has a noticeably stronger taste than Mito Natto’s other natto varieties which are packaged in plastic containers. This may be because the wara allow a lot of airflow into the natto, accelerating further growth and fermentation by the nattokin cultures.

This was the first time I’d come to Japan smuggling samples of my own New York Natto. It was intimating to offer Mito Natto company president Takaboshi-San a taste! First of all, he was quite amazed to see our natto in a glass jar; natto had never been sold this way in Japan. Next, he gave our natto a stretch and was impressed by our strong neba-neba (stretchy, slimy, sticky quality). And finally, we got a thumbs up on flavor from Takahoshi-San too! Phew, I was more than delighted to hear “This is real natto!” from an award-winning, fourth-generation natto maker. We’ve since shared our natto with many other Japanese natto producers at the national natto competition, but that’s another story.

In many places, natto rarely appears on menus of Japanese restaurants; this is mostly because natto is primarily a breakfast dish which most venues don’t serve. In Mito, local natto is served with pride at any time of day in so many eating establishments, some venues even specializing in natto-centric cuisine! Before leaving Mito, I enjoyed a lovely “Neba neba” donburi—a rice bowl topped with many ingredients with that beloved sticky, slimy texture that is so revered and believed to convey healthiness in food here.

Neba-neba ingredients in this delicious bento bowl from an unassuming train station lunch counter included: squid, salmon roe, nameko mushroom, seaweed, tororo yam, raw egg yolk and, of course, natto.

Natto News

We’re excited to add two new stores to our list of places to find NYrture Natto!

134 Southside Ave. Hastings-on-Hudson, NY 10706)

Joanne Prisco’s café & pantry, housed right inside the quaint Metro-North Railroad station celebrates women by featuring products from local female makers (thank you!) and supporting feminist community organization. Learn more about her café.

55 West Main St. Ramsey NJ 07448

Tawara Mart is the first curated Japanese grocery & bakery in NJ, located next door to the Ishii family’s Japanese restaurant, a local favorite since 1981. We’re excited to have our fresh natto among their thoughtful selection which brings an authentic, modern sensibility to break the mold of the standard Asian grocery!

NYrture New York Natto is produced by hand in NYC, fresh and never frozen, to deliver the best quality natto with maximum potential health benefits to you.

We welcome your feedback! Please share your questions & comments below!

Related links on NYrture.com:

Where to buy natto? Find stores near you

NYrture New York Natto is dedicated to providing America access to fresh, premium natto, the best natural source of Vitamin K2, nattokinase & spore probiotics.